Chapel of the Annonciade and the White Penitents

At the end of the 17th century, the city of Martigues presented an unprecedented economic boom and nearly 13,000 inhabitants. This prosperity is accompanied by an intense religious and artistic life, as everywhere in Provence. In the Jonquières district, the project to enlarge the Saint-Genest church is being carried out simultaneously with the reconstruction of a chapel for the brotherhood of white penitents of the Annonciade. The works (1661-1734) will make this chapel one of the jewels of Baroque Martégale art.

The chapel of the Annonciade, a flagship of Baroque Martégale art

The chapel of the Annonciade, a flagship of Baroque Martégale art

Notions of baroque art

The 17th century is the scene of major artistic movements such as classical and baroque art, which coexist and are often opposed. While it is true that lines, shapes, colors and light are treated differently, these styles touch the sensitivity of the viewer by their spectacular but also intimate aspect.

Baroque art is the materialization of the spirit of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, following the Council of Trent (1545-1563). In France, baroque art is steeped in classicism in the north and naturally more exuberant in the south. The chapel of the Annonciade, however, seems to be a counterexample, at least in appearance. Indeed, the discreet exterior and the single nave plan give no indication of the richness of the ornaments and interior decoration.

Baroque art is the materialization of the spirit of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, following the Council of Trent (1545-1563). In France, baroque art is steeped in classicism in the north and naturally more exuberant in the south. The chapel of the Annonciade, however, seems to be a counterexample, at least in appearance. Indeed, the discreet exterior and the single nave plan give no indication of the richness of the ornaments and interior decoration.

The brotherhoods of penitents in Martigues

The brotherhoods of penitents appear in Provence in the 13th century and form independent secular societies, their main vocation being to fulfill certain duties of devotion and charity individually and collectively. The penitents participate in the life of the parish, sing the services, assist the sick, bury the dead, make processions. Each brotherhood is very regulated and is characterized by its costume and its chapel, place of devotions but also of meetings. During ceremonies and processions, penitents cover themselves in a loose garment called a sack and a hood pierced through the eyes.

These brotherhoods numbered four in Martigues at the end of the 17th century. Each parish has a company of penitents who hold a meeting place separate from the church. The color of their clothes determines their name: white penitents at Ile and Jonquières, blue penitents at Ferrières. As for the black penitents, we do not know their meeting place. The brotherhood of white penitents of Jonquières is placed under the invocation of the virgin of the Annonciade. In the 18th century, their religious aspect faded, the brothers gathered for the pleasure of being together. These brotherhoods disappeared during the French Revolution to reconstitute themselves in the 14th century.

These brotherhoods numbered four in Martigues at the end of the 17th century. Each parish has a company of penitents who hold a meeting place separate from the church. The color of their clothes determines their name: white penitents at Ile and Jonquières, blue penitents at Ferrières. As for the black penitents, we do not know their meeting place. The brotherhood of white penitents of Jonquières is placed under the invocation of the virgin of the Annonciade. In the 18th century, their religious aspect faded, the brothers gathered for the pleasure of being together. These brotherhoods disappeared during the French Revolution to reconstitute themselves in the 14th century.

The altarpiece

One of the most important elements of the Annonciade chapel is the high altar altarpiece. Majestic work of 7.91 m high by 8.28 m wide, it is composed of the altarpiece itself, built in walnut, alder, beech and carved gilded and polychrome godson wood, as well as three paintings in connection with the theme of the life of the Virgin.

The tabernacle (cabinet above the altar housing the ciborium containing the hosts) seems to have been designed between 1661 and 1671, during the construction of the chapel and put back in place in the altar of the current altarpiece made in 1702 by Étienne and Claude Darbon, master carpenters from Martigues. Corresponding to a codification established by the Council of Trent, the altarpiece presents a central painting depicting the Annunciation. The two lateral bays are decorated with a painting representing respectively The Nativity of the Virgin Mary and the Presentation of the Virgin in the temple.

The tabernacle (cabinet above the altar housing the ciborium containing the hosts) seems to have been designed between 1661 and 1671, during the construction of the chapel and put back in place in the altar of the current altarpiece made in 1702 by Étienne and Claude Darbon, master carpenters from Martigues. Corresponding to a codification established by the Council of Trent, the altarpiece presents a central painting depicting the Annunciation. The two lateral bays are decorated with a painting representing respectively The Nativity of the Virgin Mary and the Presentation of the Virgin in the temple.

The furniture of the Chapel

Little remains of the original furniture. Some crosses and processional lamps are on display at the Martigues History Gallery. The rest must have been melted down or destroyed during the Revolution. We still have the stalls and the main wooden entrance door recovered from the first chapel. The inscription of June 4, 1936 marks the date of installation of this sculpted door. It is signed Honoré Granier.

The walnut stalls are benches that allowed penitents to follow the pantry from the side benches. They were made between 1651 and 1655 by a carpenter from Martigues (André Ollivier) and sculpted by a Marseille craftsman (Louis Bremiard). The prior's seat is distinguished from the rest by a canopy decorated with a painted and gilded wooden tympanum showing an Annunciation between two kneeling white penitents.

The walnut stalls are benches that allowed penitents to follow the pantry from the side benches. They were made between 1651 and 1655 by a carpenter from Martigues (André Ollivier) and sculpted by a Marseille craftsman (Louis Bremiard). The prior's seat is distinguished from the rest by a canopy decorated with a painted and gilded wooden tympanum showing an Annunciation between two kneeling white penitents.

Wall decorations: 1734

The initial program provided for simple whitewashed walls decorated by the stalls and paintings of the first chapel. We have lost all trace of these first works, only the stalls are present. The decoration will be transformed at the beginning of the 18th century. In 1734, monumental frescoes were completed illustrating the cycle of the life of the Virgin and of Christ. They are signed Blaye father and son, as evidenced by the inscription on the west wall. Of these monumental decorations do not remain The Dormition of the Virgin, The Wedding Feast at Cana, Jesus among the Doctors and the Immaculate Conception on the south wall, to the left. We can also see on the right, Saint Ursula, patroness of the brotherhood of penitents, a priori carried out during the 1966 restorations.

In the center, an apparently mythological scene shows Minerva and Hercules. Made during the Revolution, it is in fact an allegory of Reason and Force, discovered under a painting of the Nativity of the Virgin.

In the center, an apparently mythological scene shows Minerva and Hercules. Made during the Revolution, it is in fact an allegory of Reason and Force, discovered under a painting of the Nativity of the Virgin.

Ceiling decoration: 1677

After the vaults collapsed in 1664, we opted for a simple roofing of canal tiles on a wooden frame. In 1677, a carpenter from Aix, Jean-Claude Boyer, commissioned a sumptuous flat ceiling in painted and gilded fir wood which fell like a basket handle on the walls. The painted decorations are said to have been executed after the drawings of Michel Daret, painter from Aix, son of the great Baroque painter Jean Daret. This ceiling also serves as the framework for a series of 5 oil paintings on canvas, relating to the life of the Virgin and attributed to the painters Barthélémy Donneau de Martigues and Anthoine Ollivier of Marseille. The original paintings are The Assumption of the Virgin and The Coronation of the Virgin, the rest date from the 1966 restoration campaign.

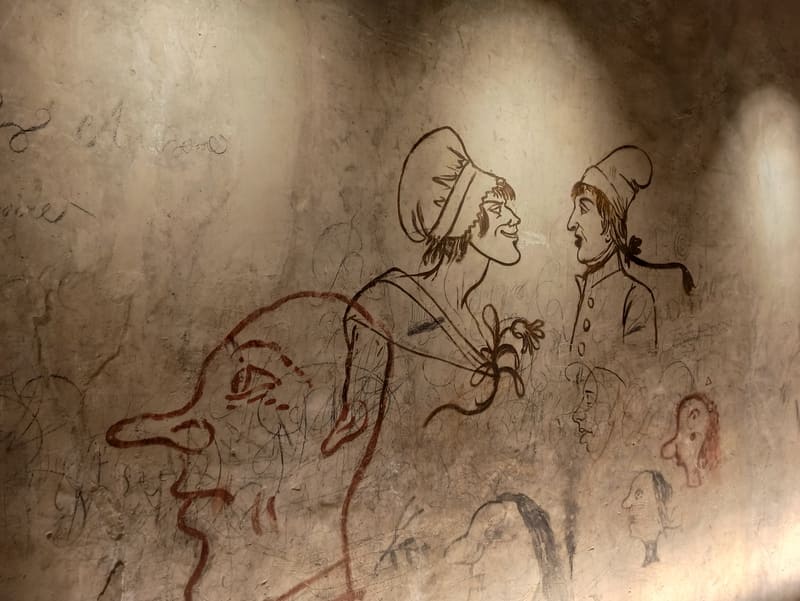

The graffiti tribune

The walls of the gallery are covered with graffiti drawn in charcoal, red chalk or knife point. These drawings bear witness to a little over three centuries of human memory carved in stone. The first floor was accessed via a freestone spiral staircase. The gallery opened onto the nave by two bays until the altarpiece was installed in 1704. Vases embedded in the walls were intended to improve acoustics. The vault preserved here remains the only witness to the roof collapsed in the nave in 1664. From its origin, this space became a privileged place for votive dedications. Dates are affixed from 1664. Then come representations of warships and fishing vessels from the second half of the 17th century. There are also litanies and motifs associated with the iconographic register of penitents, in particular the skulls and devils, as well as the figure of the praying virgin.

Other motifs, several series of windmills testify to their importance in the daily life of martégaux until the middle of the 20th century. Human figures could represent local custom, an armed rider, men with hats, pipes. The initial surnames and signatures bear witness to the names of the faithful or of visitors anxious to leave their mark on posterity. Finally, a revolutionary graffiti is distinguished by its size and its beautiful craftsmanship: a caricature of the revolutionary era, the restrained face of a man wearing a Phrygian cap, wearing a jacket with buttons and his hair tied in a ponytail, faces with the ironic contentment of a woman's face wearing a fringed charlotte.

Other motifs, several series of windmills testify to their importance in the daily life of martégaux until the middle of the 20th century. Human figures could represent local custom, an armed rider, men with hats, pipes. The initial surnames and signatures bear witness to the names of the faithful or of visitors anxious to leave their mark on posterity. Finally, a revolutionary graffiti is distinguished by its size and its beautiful craftsmanship: a caricature of the revolutionary era, the restrained face of a man wearing a Phrygian cap, wearing a jacket with buttons and his hair tied in a ponytail, faces with the ironic contentment of a woman's face wearing a fringed charlotte.